On the early morning of July 23, 1999, in Tulia, Texas, nearly 33 percent of the city’s Black male residents were arrested.

Tulia, a sleepy town of 5,000 in the Texas panhandle, was shocked awake before dawn when 46 residents were roused without warning and dragged to jail, many still undressed from sleeping in their homes, some with no shoes. They were also paraded before a cavalcade of news cameras that had been alerted prior in order to humiliate the detained.

Forty of those arrested were Black, and the other six had ties to the Black community.

All were charged with dealing powdered cocaine based on the lone testimony of one white police officer. The white officer, Tom Coleman, who had a racist history of using slurs like the n-word, provided no fingerprints, no videos, no wire audio, no marked money, and no independent witnesses. Despite grossly inadequate evidence, and the absence of drugs, money, weapons, or other signs of drug dealing found on the accused, Coleman’s testimony produced 38 wrongful convictions — almost all Black residents — by all-white or mostly white juries, and condemned the convicted to a collective 750 years in prison. Many of those charged, most completely innocent, plead guilty just to receive a lesser fine, probation, or lower sentence.

Nearly every Black person in town had a relative or friend arrested or convicted.

Four years after the arrests, with 16 people still in prison, a district judge finally overturned all 38 convictions based on the uncorroborated and discredited testimony of Coleman. On June 16, 2003, after spending four years of their lives in prison for crimes they did not commit, 12 of those convicted — 11 of them Black — walked mostly free, still shackled by bail, but belatedly liberated to hug loved ones in fresh air and sunlight.

It remains one of the biggest drug stings in local history.

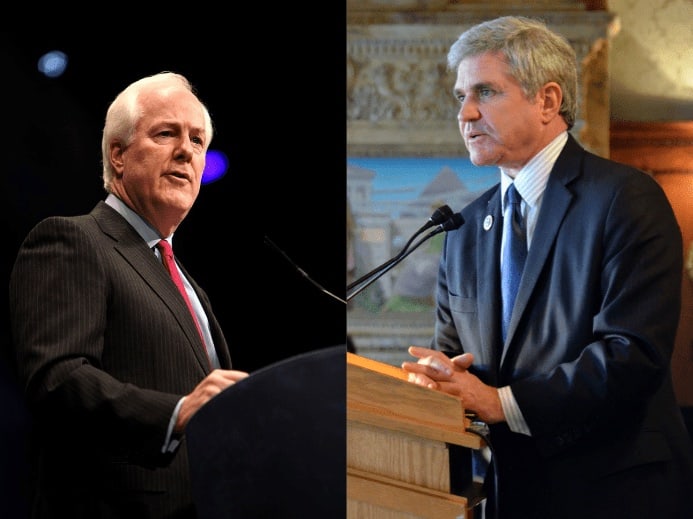

The state’s presiding political officers over this stained and long denied justice — the racist mass arrests of Black people in Tulia — were then-Texas Attorney General and now U.S. Sen. John Cornyn, and his former Deputy Attorney General for Criminal Justice, U.S. Rep. Michael McCaul.

Months before the atrocities in Tulia in 1999, McCaul joined Cornyn’s office to preside over criminal justice cases, and months after, Cornyn awarded Coleman, the white police officer, “Lawman of the Year” for his unreliable testimony that led to the arrests of 46 people, overwhelmingly Black. However, as evidence quickly mounted against Coleman’s faulty evidence and racially motivated action, calls became louder to free those in prison.

As the state’s leading prosecutors, Cornyn and McCaul had unique latitude in opening an investigation, taking over the case, and overturning the convictions in Tulia. Instead, they intentionally delayed action and sat on the sidelines for years.

With a slow-moving federal probe by the U.S. Department of Justice, local civil rights lawyers and national groups like the ACLU, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and the William Moses Kunstler Fund for Racial Justice continuously demanded Cornyn take state action to vacate the convictions rooted in uncorroborated evidence and racial prejudice.

In response to the ACLU of Texas’ call for Cornyn to investigate “the ethnic cleansing of young male Blacks from Tulia,” then-deputy attorney general McCaul, who oversaw criminal justice efforts for Cornyn like that of Tulia, told the civil rights group that a state investigation would be “duplicative” of the federal inquiry. He later falsely claimed that state law prohibited the attorney general from investigation without an invitation. When questioned in a Texas House Judicial Affairs Committee hearing, McCaul admitted that no such statute existed, and similar interventions had been made prior in other cases. Cornyn deflected with similar excuses of waiting for the federal investigation to move forward.

The ACLU of Texas said in a written statement that Cornyn had failed to uphold Texas’ laws and constitution by not honoring the Hate Crimes Act. “[Cornyn] has not defended the civil rights of Tulia, Texans,” they wrote.

Cornyn and McCaul deliberately failed to act until it became politically expedient. It was not until late August 2002 — more than three years after the initial arrests — that Cornyn opened an investigation into the drug sting. He did so as he faced embattled criticism for inaction on the matter, and as he was mounting a bid for an open U.S. Senate seat against Ron Kirk, the Black Democratic mayor of Dallas.

Years and months overdue, the decision failed civil rights groups that had long waited for the convictions to be overturned. An investigation was no longer enough. Vanita Gupta, a lawyer with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund who helped bring national attention to Tulia, urged Cornyn to completely take over the case and overturn the convictions — actions within his authority as attorney general.

“It smacks too much like kind of a political solution for Cornyn, rather than a genuine commitment,” Gupta said in 2002. “Cornyn has known about these cases for three years. If he wants to see justice done, then he knows that he needs to take over these cases.”

In April 2003, the state probe was surreptitiously ended with no reports made public. One month later, a district judge stepped in for Cornyn and McCaul’s inaction, and overturned the Tulia convictions. In early 2005, Coleman, the white officer who Cornyn named “Lawman of the Year” and whose sole testimony served as the foundation for the Tulia convictions, was convicted of “blatant perjury” and sentenced to 10 months of probation.

As the nation faces sweeping protests against racial injustice and the disproportionate violence and incarceration of Black people, the miscarriage of justice committed in Tulia holds particular valence.

In November, Texas voters will face the option of uprooting complicit political actors who failed to deliver racial justice. McCaul and Cornyn will both face Democratic challengers this fall.

Mike Siegel, a civil rights lawyer and former public school teacher, made waves in 2018 for coming within 5 points of unseating McCaul, now a member of Congress for Texas’ 10th congressional district. Siegel is challenging him again in 2020 to finish the job.

Siegel has a long history in the fight for racial justice. He served as a plaintiff in a 2011 ACLU lawsuit to stop excessive police violence against protestors. In 2018, Siegel successfully pushed Waller County to reverse a policy that would have suppressed the voting rights of students at Prairie View A&M, a historically Black university. This year, he has forcefully stood with the Black Lives Matter movement, and denounced the systemic killings of Black people.

“Our campaign is taking on Mike McCaul because #BlackLivesMatter & because undoing institutional racism is the task at hand in this historic moment,” Siegel wrote in a Twitter thread about the Tulia case. “As a civil rights attorney, I’ve fought against racist police policies & won.”

Siegel is in a July 14 runoff election with Pritesh Gandhi, a medical doctor who is running to Siegel’s right.

Cornyn will also face a Democratic political challenge from either Sen. Royce West, a Black 14-term state senator from Dallas, or MJ Hegar, a former U.S. Air Force helicopter pilot. The winner will be determined by the July 14 runoff election.

West has spent much of his legislative career focused on criminal justice reform — helping ban racial profiling in policing and putting dashboard cameras in police vehicles; authoring a state law to increase the use of body cameras by police; and he has recently attended protests against police brutality. West also carries the endorsements of his former Senate primary opponents, mostly people of color, prominent federal elected officials of color, a significant number of the state’s Black and Brown legislators, and several Black and Latinx political clubs and caucuses. Hegar, a white woman who previously donated to Cornyn and voted in the 2016 Republican primary, has also recently called for reform. Hegar is buoyed by her support from older white and independent voters, in contrast to West’s support from Black and younger voters, according to polls.

Vanita Gupta, the same civil rights lawyer who asked Cornyn to take over the case in Tulia and the same lawyer whose legal team ultimately helped overturn the Tulia convictions in 2003, exposed that Cornyn — almost 20 years later — still fails to understand the reality of systemic racism and implicit bias at a U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee hearing just last month.

Cornyn and McCaul were complicit in looting Black people of opportunities to work and build wealth for years, in leaving Black children without parents as they were forcibly incarcerated under false pretense, and in condemning innocent people to years in prison by sweeping justice under the rug. Cornyn and McCaul had the ability to press to overturn the convictions and remedy the racist mass arrests of Black people in Tulia. Despite all evidence to the contrary, they failed to act, and for that, they failed Texas.

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons / McCaul government website

Chris covers Texas politics and government. He is a Policy Advisor for Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo and a graduate student at Harvard University. Previously, Chris served as Texas State Director and National Barnstorm Director for Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, and as a Political Advisor for Beto O’Rourke. Born in Houston, Texas to immigrants from Hong Kong and Mexico, he is committed to building political power for working people and communities of color. Chris is a Fulbright Scholar and a graduate of Rice University.