The 2022 hurricane season is officially upon us, with Texans once more preparing themselves for the worst. As hurricanes increase in force due to the effects of climate change, so do the intense flooding and winds that accompany the storms become an even greater risk to Texans living near the Gulf of Mexico. The danger is particularly great for those in the vicinity of Galveston Bay, where the high concentration of refineries and chemical processing plants could result in an environmental disaster of epic proportions. Now, after over a decade of lobbying efforts, the House of Representatives has finally passed a bill that allows for the commencement of the ambitious project necessary to prevent this catastrophe.

Shepherded by the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, the estimated-$31 billion bipartisan proposal was included in the Water Resources Development Act of 2022 that overwhelmingly passed on June 8. Only 37 overall representatives opposed the legislation, yet five Texas Republicans helped make up that minority: Lance Gooden, Troy Nehls, Pat Fallon, Van Taylor, and Chip Roy.

The project is the massive engineering plan proposed by the Coastal Texas Protection and Restoration Feasibility Study, a six-year cooperative effort between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Texas General Land Office. More commonly known as the Ike Dike, the project was first conceived of by Texas A&M at Galveston marine sciences professor Bill Merrell, who was concerned with the security of the Houston Shipping Channel in the aftermath of the devastating Hurricane Ike in 2008.

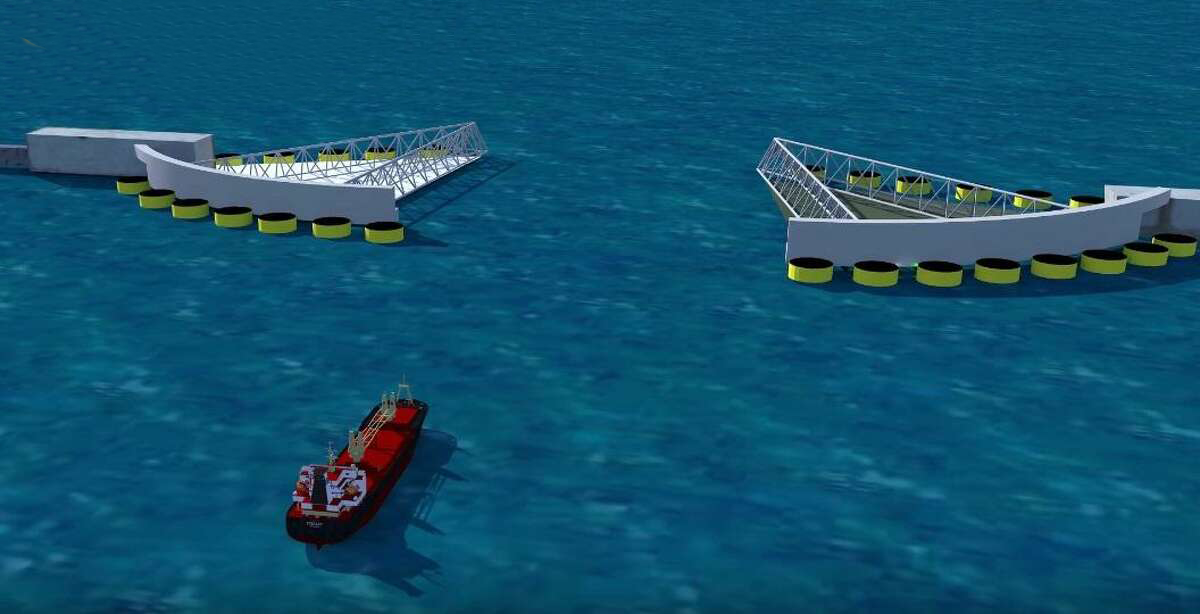

In the years since, this “coastal spine” to protect nearby residents has taken on many forms, its likely final arrangement consisting of huge 650-foot wide floating gates that close to prevent storm surges from flooding the Bay’s waters as well as the construction of artificial beaches and dunes in the Galveston area to protect local properties. The coastal project as currently designed would be the largest civil engineering project ever proposed in the United States.

The project has not only become a symbol of Texan natural disaster mitigation and climate resiliency but also representative of the types of nonpartisan, common sense infrastructure projects that used to pass in the less gridlocked Congress of yesteryear. “When you have a senator like Senator Cruz who is explicitly saying he’s not going to ask to get the resources that Texas needs out of budget bills, it undermines our ability to get all this great stuff that keeps Texas a healthy, thriving, wealthy, working state,” said writer Evan Mintz in a discussion on the podcast City Cast Houston.

A former Houston Chronicle editorial board member, Mintz has long been arguably the most vociferous, high-profile media advocate for the project. “My banging on the drum is not just about building the Ike Dike but also a larger philosophical message that we need our representatives to care about our state and not just what does well in the big culture wars happening on cable news,” Mintz maintained.

Some progressives still have valid fiscal and environmental concerns about the Ike Dike. Though the House legislation approves the project, it does not provide it funding, which must be provided either through Congressional appropriations or politically-challenging state and municipal taxes. “Once this project is authorized, nobody knows how it’s going to be funded,” said Amanda Fuller, director of the Texas Coast and Water Program at the National Wildlife Federation, in an interview with the Texas Tribune.

The project also prioritizes the defense of monetary value over that of people, which could lead to the protection of rich peoples’ properties at the expense of poor peoples’ homes. Others also claim that the Ike Dike could serve as a net-negative to environmentalist efforts by damaging influence over the Galveston Bay ecosystem by endangering the region’s turtle, bird, and fish populations as well as publicly subsidizing the long-term protection of oil and gas infrastructure. Nonetheless, advocates believe that the pursuit of the project’s main goal, protecting as many Texans as possible, outweighs the negatives.

Whether the project ever comes to pass still technically remains to be seen, though the Senate is exceedingly likely to consent to its construction, the full-shielding effect of which will probably not come to fruition for twenty years. In the meantime though, the slow law-making process will continue chugging along, and Texas residents will continue prepping for the Chernobyl-level event that may or may not come.

Photo: Army Corps of Engineers